Rites of passage

We explore the rites of passage we all go through, with a focus on Chesterfield life.

Birth - welcome to the world

Being born - the first rite of passage - is not always easy but it is the start of a journey.

In Chesterfield, as everywhere, birth is certified, commemorated and celebrated, because it is important to mark the beginning of a new life.

There is, of course, the happiness of welcoming a new baby into the family and community with celebrations and gifts to remember this special time. However, we mustn’t forget that this rite of passage can be a difficult period for baby, of course, but also for the parents. Birth and infancy is a joyous but often challenging time.

A seated baby bundled up in a dress cape and hat, inscribed on the back ‘In affectionate remembrance of little Arthur for his Aunt Agnes’, c1890.

Two nurses watching over a new-born baby in the Premature Ward, Scarsdale Maternity Hospital, 1989.

A new baby is also a life-changing event for the parents. These guidelines from Derbyshire County Council’s Infant Welfare Centre show the kind of advice given to mothers in the 1930s.

School days

Childhood brings its own firsts and special moments. Perhaps it’s a favourite toy or that first treasured book or comic. Childhood also brings with it memories of our school days.

The Education Act of 1870 highlighted that Education was a right and not a privilege. In doing so it made schooling a rite of passage for every single child in the United Kingdom.

From 1873 free and compulsory education was provided for all children in Chesterfield, from the ages of 4 to 13.

We all remember our school days; knees knocking with nerves on the first day, the aromas of the schoolroom, the smell of school dinners.

But of course it wasn’t all study, tests and exams, there are also the happy memories of rare treats like sports days and school trips.

For many children in the past leaving school marked the end of childhood and the beginning adult life.

A Ragged School Attendance Card for Elsie Elliot, 1910.

This is the end of school report for CH Sadler from Chesterfield Grammar School, dated 1928. Although his Arithmetic is ‘Painstaking’ everything else seems quite positive. His form master Mr Thorne has written 'Has done well. I wish him every success. He has our best wishes. We are sorry to lose him.’

Growing up, going out

Starting work would have been a daunting experience for a young person.

Employed or apprenticed in very junior positions, these young employees had to learn very quickly how to get on in their working life. Taking a little criticism and teasing in their stride, looking forward to what made it all worth while - that Friday pay packet.

Because, of course, growing up and being young in the twentieth century was also about going out. Chesterfield had a number of venues to enjoy yourself. Cinemas like the Odeon or the ABC, dance halls like the Rendezvous and the ‘Vic’ (Victoria Ballroom).

As the twentieth century progressed being young became a time for new experiences and having fun. It really saw young people embracing music, fashion and popular culture as never before.

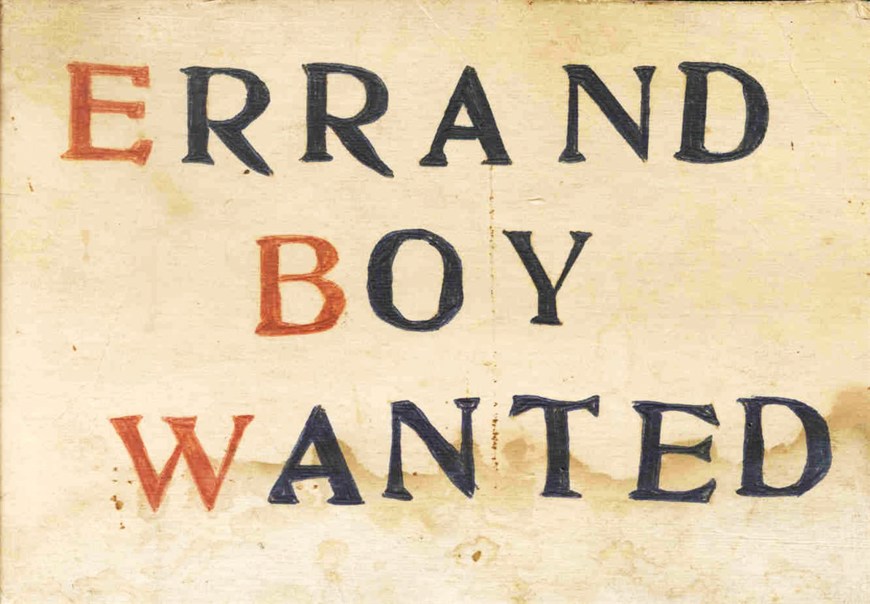

Many boys on leaving school at 12 or 13 years of age would find employment as errand boys for local grocer’s shops and merchants.

In the 1920s the company Victoria Enterprises took full advantage of the development of Knifesmithgate Street to develop the existing cinema and billiard hall. The final complex was completed in 1930 and included a café and a ballroom for 500 people. The ’Vic’ became a popular local venue for dances, wedding receptions, company balls and much more. During the 1960s it saw the likes of The Kinks, The Hollies, The Who and The Small Faces perform on its stage.

That first trip away from home alone is also an important rite of passage.

On 14 July 1939 Robinson’s celebrated their centenary by taking almost 3,700 Robinson’s employees on a trip to London which included tours of Westminster Abbey, the tower of London and London Zoo. For many of the young men and women who worked at Robinson’s it was their first time outside of Chesterfield and an unforgettable day. In the photograph above we see a crowd of Robinson’s girls heading to the station to catch a specially commissioned train to the capital. In stark contrast a few months later Britain was at war and many young men found themselves taking the same trip but this time to go to their regiments or report at training camps for military training.

Tying the knot

The idea of rites of passage immediately brings to mind marriage and making a home together.

Unlike today, grand white weddings at the turn of the twentieth century were almost always reserved for the very wealthy. Everyday folk would be more likely to dress up in their Sunday best for a small celebration with family and friends.

Later, the trend for a fancier occasions and outfits became more popular. Still, most couples focused on saving money for their life together rather than spending a fortune on one day.

The cover of ‘Home Chat’ magazine, December 1925. Focusing on the Winter Wedding. Showing the growing interest in bridal fashions for a wider market.

Here the young bride and groom pose beside an Austin wedding car, with the driver opening the door and guests surrounding them,1948.

Far more important than the wedding day, for the young couple, was making a home of their own and settling down.

A first home is an important landmark, providing a harbour from the storm of everyday life and becoming a place to raise a family.

In the twentieth century, most especially in the 1920s and 30s, huge improvements were made across Britain, providing better quality social housing for the working classes.

In the post war decades of the 1950s and 1960s a greater number of young families were able to get on the property ladder by taking a mortgage and become home owners themselves.

St Augustine's Crescent Housing Scheme 1995.1157

After the First World War, the Addison Act of 1917 aimed to provide decent housing for working people throughout the UK. This act led directly to the first houses being built by Chesterfield Borough Council, on St Augustine’s Road in 1920. Government subsidies were increased by the 1924 Housing Act to provide even more accommodation for low paid workers and their families. These houses had a parlour, living room, scullery and three bedrooms and offered families the opportunity to live in clean, safe and modern accommodation for the time.

Saying goodbye

The final rite of passage is, of course, death.

Some will have had, as they say, ‘a good innings’ but others are tragically taken far too soon.

Funerals are important rituals as a means of paying respects and commemorating life. They are a chance to say goodbye to the ones we have loved and cherished.

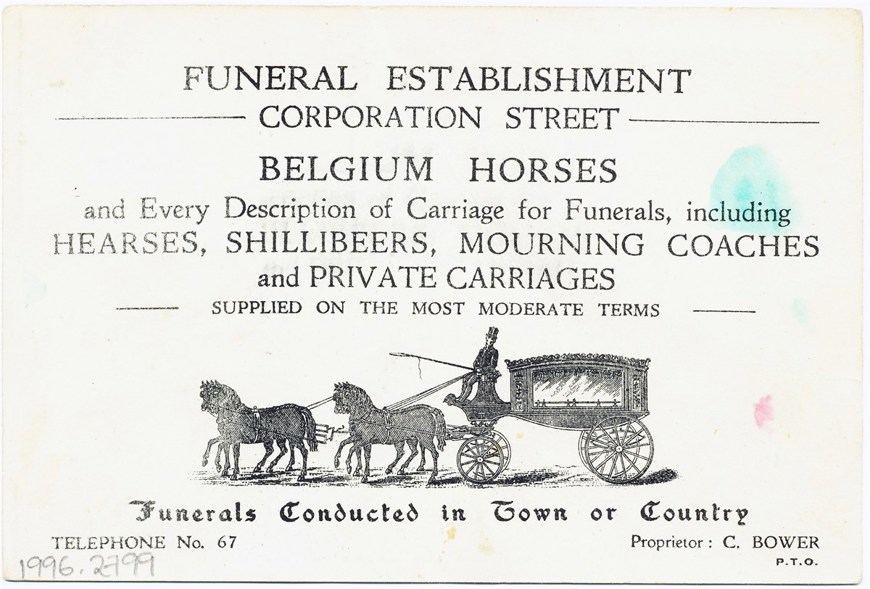

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, funeral directors often operated alongside or as part of a joinery or carpentry business. Mourning houses were also established, where everything a family needed could be organised.

An advert for a funeral establishment on Corporation Street, Chesterfield in the late nineteenth century.

A glass sided hearse from Wetton Funeral Directors, 1910.

The small boys seated at the side give an idea of the size of this carriage. The boy on the left is Alan Wetton, the funeral director’s son.

Photograph of the funeral procession of Chesterfield MP James Haslam, July 1913.

Here you can see a traditional Edwardian funeral bier pulled by horses.

The Derbyshire Times noted that, ‘The day of James Haslam’s funeral saw the Chesterfield streets lined with mourners.’

Born at Clay Cross in 1842, Haslam worked at the local colliery from the age of ten. He later became a leading figure in the struggle to improve conditions for miners, founder of the Derbyshire Miners’ Association and, from 1906 to 1913, MP for Chesterfield.

He was a much-loved local figure. A statue of him stands outside the NUM buildings on Saltergate, Chesterfield.

Funeral Cars lined up for the nine victims of the Markham Colliery Explosion, 1937

On Thursday 21 Jan 1937, at Blackshale Pit, Markham Colliery, an explosion was caused by a spark from a coal cutting machine igniting firedamp (methane gas). Rescue Services from Chesterfield and Mansfield rushed to the scene but seven men died instantly and later two more miners died at the Chesterfield Royal Hospital.

The next year an even greater tragedy occurred when, on 10 May 1938, 79 men lost their lives in an explosion at the same colliery.