Crime and punishment

This exhibition looks at how crime and punishment has changed over the years in Chesterfield and beyond.

A force for the town

Chesterfield’s police force was formed in 1836 in response to a government act. Every Borough was required to form a watch committee responsible to organise ‘sufficient number of fit men ... for preserving the peace by day and night’.

Seven constables and an inspector were employed, however they were little more than a night watch. The force was not a professional unit and there were problems with retaining men and with drunkenness on duty. It was not until 1846, when two day policemen were appointed, that the force came under stricter control.

The police were not only responsible for maintaining law and order but also enforced the local bye-laws as well as providing the town’s fire brigade.

Drunkenness and neglect of duties were common complaints about Chesterfield’s early police. In March 1875 Constable Thomas Canning was found asleep, drunk in the kitchen of the Blue Bell Inn on Holywell Cross while on duty. This was not his first offence since joining in February 1874 and he was allowed to resign immediately.

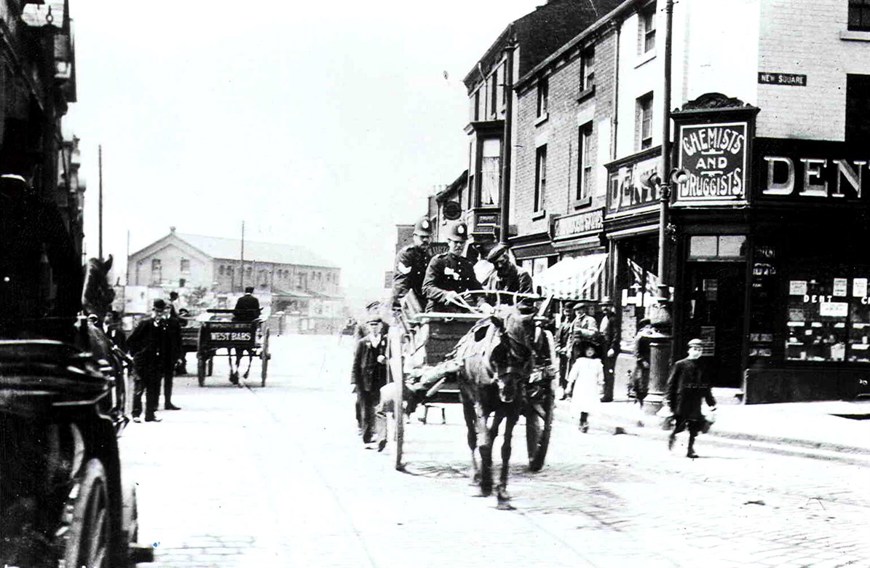

Policemen escorting a prisoner to the police station, c. 1900. Police officers were given financial rewards for exceptional work leading to an arrest or acts of bravery. PC Thomas Ingleton, for example, was awarded 10s 6d in 1891 for apprehending John Gaunt in the act of breaking into Fearnchurch Bros. shop on Holywell Cross.

The areas surrounding Chesterfield Borough were not covered by the town’s police force, but by the County Police. They were formed in 1857 and had a station based in Chesterfield.

Behind bars

Prisons were not originally used as a form of punishment but to hold those awaiting trial. However, by the end of the eighteenth century, imprisonment was increasingly used as a sentence. By the mid nineteenth century, it had largely replaced other types of punishment, such as transportation.

Conditions varied from prison to prison. However, many were overcrowded, cold and unhygienic. All prisoners were required to work but many prison sentences included ‘hard labour’, usually pointless, demanding tasks such as turning a crank or treadmill.

The end of the nineteenth century saw a change in the way offenders were treated. Improvements had been made to prison conditions all prison work was required to be productive. There was also a greater emphasis on the reform of prisoners.

A section William Senior’s map, 1637, showing Chesterfield’s House of Correction. It opened in 1614 on the banks of the River Hipper and served the Scarsdale area. People from the High Peak were also kept there until 1711 when a house was built at Tideswell. The house was intended to set to work ‘all such idle, wandering and other disordered persons as shall be apprehended’.

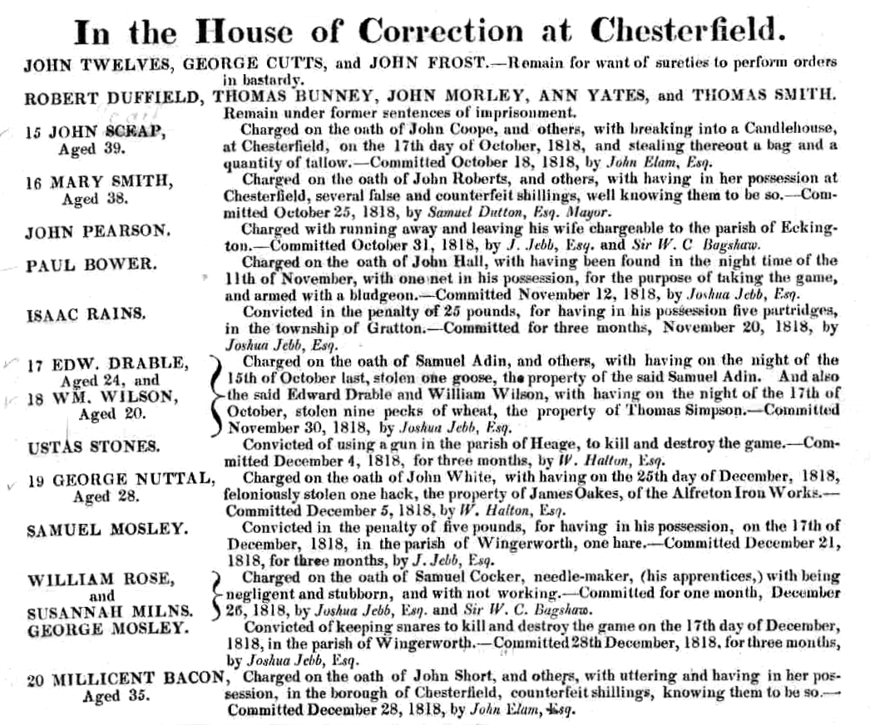

A list of prisoners (above) held in Chesterfield’s House of Correction, January 1819. The House of Correction eventually merged with the prison system and by the eighteenth century in Chesterfield, petty criminals with short sentences were held there. By 1860 the house was no longer in use.

The majority of criminals from Chesterfield served their time at the County Gaol in Derby. Vernon Gate Gaol was built in 1823 and replaced Friar Gate Gaol which was over crowded, badly ventilated and was condemned as ‘insufficient and insecure’. Like many nineteenth century prisons, it was built with a wheel layout with the chapel and governor’s house in the centre and seven cell wings. It closed in 1919 and later became a greyhound track!

Those prisoners at Derby Gaol who were given ‘hard labour’ either used the treadmill to grind wheat or picked oakum (untwisting tarred rope which caused fingers to bleed). The 1898 Police Act abolished the treadmill and demanded that all prison labour should be productive. Hard labour was abolished in 1948.

Debtors were also sent to prison where they would be held until the balance was paid. Chesterfield’s debtors’ prison was underneath the town hall located in the Market Place until 1850 when provision was made within the new Municipal Hall on South Street. In 1869 imprisonment for debt was abolished.

Chesterfield Borough police

Between 1892 and 1920 the borough of Chesterfield expanded greatly from 322 acres to over 8,000. The Borough Police also grew in size in order to be able to cover the larger area and bigger population. The number of officers increased from 17 men in 1890 to 65 in 1922. In 1925, the first police woman, Jessie Webster, was appointed.

During the Second World War the police took on additional duties, including organising air raid precautions and enforcing wartime regulations.

In 1947, the police service was reorganised and Chesterfield Borough Police were amalgamated with Derbyshire County Constabulary.

Police call boxes and pillars were introduced across the Borough in May 1933. They contained a publicly accessible telephone, directly linked to the police station so not only could the constable on the beat easily keep in contact but members of the public could also summon the police in an emergency. The boxes themselves were used by officers as a place to write reports or have their lunch.

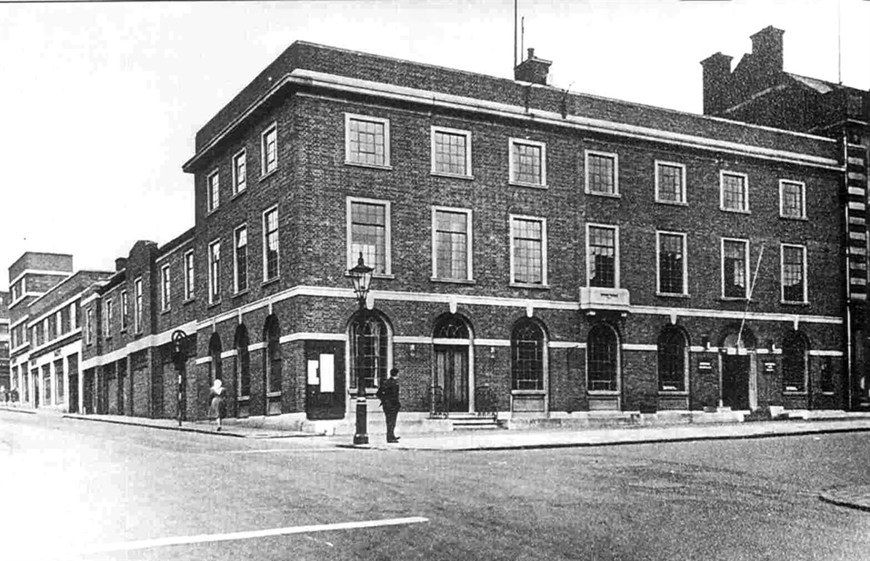

Chesterfield’s police station (pictures above) was first located within the Municipal Hall on South Street which also housed the Borough magistrates’ court. However by the 1920s, a larger building was needed and a new police and fire station was erected on New Beetwell Street, opening in 1926. This picture shows the building after its extension in 1937.

Police officers preparing equipment to lay telephone cables during the Second World War (above). Although the police were an important part of civil defence, some officers were called up for the armed forces. The Police War Reserve was set up to provide extra men and consisted of retired officers and men in reserved occupations. The Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps was also formed, providing typists, telephonists and drivers. Many women joined the police force after the war.

Chesterfield Borough Police purchased a van for the transport of prisoners in 1923 but it was not until the 1930s when the force acquired its first patrol car.

Court justice

From the mid nineteenth century until the 1970s, the justice system in England operated three main types of court.

The petty courts dealt with minor offences on a local level ranging from drunkenness to traffic infringements. The court met regularly and so the accused were dealt with swiftly. The petty courts also referred more serious cases to the quarter sessions.

The quarter sessions were held four times a year within each county and a session for Derbyshire was held at Chesterfield until 1857. Criminal cases such as assault and burglary were heard at these trials.

Serious crimes, such as murder and rape, were dealt with at the assize court. England and Wales were split into eight ‘circuits’ covering a group of counties. Judges would travel within each area, hearing cases twice a year in each county. The assize court for Derbyshire was at Derby.

Petty and quarter sessions were presided over by Justices of the Peace. These were unpaid magistrates, usually landowners, appointed by the Lord Chancellor. Violet Markham (pictured above) was mayor of Chesterfield in 1927 and served as a local Justice.

When the Market Hall opened in 1857, it contained a magistrate’s court for the hearing of petty sessions and the summer quarter session. These trials were previously held at the Town Hall in the Market Place. The Municipal Hall on South Street also served as a venue for Borough petty sessions.

The police station on New Beetwell Street opened in 1926 and housed a police court to hear petty sessions concerning crimes within the Borough.

Crime in the news

“At the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for this county ... George Longley, an apprentice, convicted of obtaining money from a party of the 59 regiment of foot at Chesterfield, was ordered to be imprisoned 6 months and the be publicly whipped at Derby on Friday next.” Derby Mercury, 25 April 1805.

“George Wright alias William Turner for obtaining under false pretences, 2 hats, the property of James Davenport of Chesterfield. The prisoner pleaded guilty. To be imprisoned for the House of Correction for six months and kept to hard labour.” Chesterfield Gazette, 19 July 1828.

“Elizabeth Hart was brought up on a charge of assault preferred against her by Mercy Bays, lodging house keeper at the top of Glumangate ... as a set off against the charge, Hart ... said that Bays kept a very bad house in harbouring them for they were all girls of the town. This excited the landlady who … stated to the magistrates that the quarrel originated in picking of pockets and dividing the spoil…….The magistrates committed Hart to 14 days imprisonment…” Derbyshire Courier, 16th July 1836.

“George Bradley, 47, was charged with stealing on the 8th day of May last at Chesterfield, one shirt and one pair of stockings, the property of the Guardians of the Chesterfield Union. Pleaded guilty and to a previous conviction. The chairman told him that he had only just come out of prison and had rendered himself liable to transportation. Sentence: Six months imprisonment”. Derbyshire Courier, 3< sup>rd July 1852. p>

“William Miller, aged 16, collier, was indicted for stealing a horse-rug, the property of Henry Naylor at Brampton on 19 December ... The prisoner was found guilty of receiving the rug but was recommended to mercy and he was sentenced to 14 days imprisonment.” Derbyshire Times, 7 January 1871.

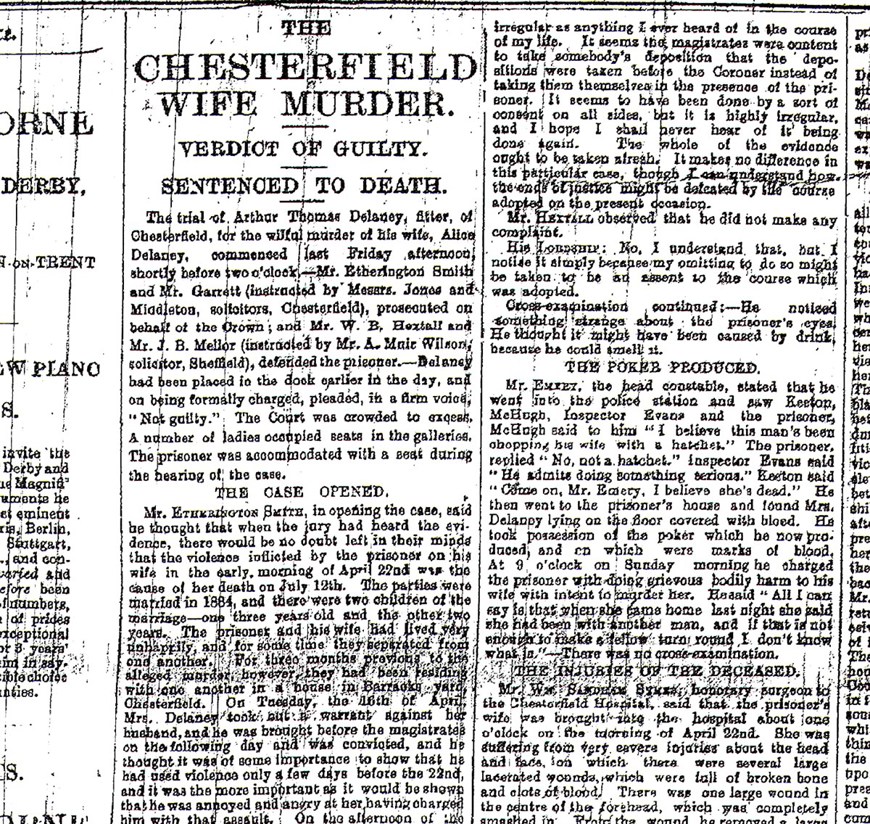

“The trial of Thomas Arthur Delaney, fitter of Chesterfield, for the wilful murder of his wife, Alice Delaney ... His Lordship, having assumed the black cap, said ‘Arthur Thomas Delaney, the jury upon the clearest evidence ... have found you guilty of a terrible crime and it is my duty to award an awful punishment for it’” Derbyshire Courier, 28 July 1888. Delaney was hanged at Derby Gaol two weeks later.

“At the Derbyshire Assizes ... the hearing was commenced by Mr Justice Pullimore of what has become familiarly known as the Chesterfield Baby Farming Case. The accused, Betsy Newton, aged 64, and Julia Hooper, aged 32, … were indicted for the manslaughter of a male child known as Claud Roberts or Claud Newton of Chesterfield ... It was the culpable and cruel neglect of a baby whom they had in their charge” Derbyshire Courier, 4 March 1905. The women had received a total of £35 for adoption of the child. They were sentenced to ten years penal servitude.

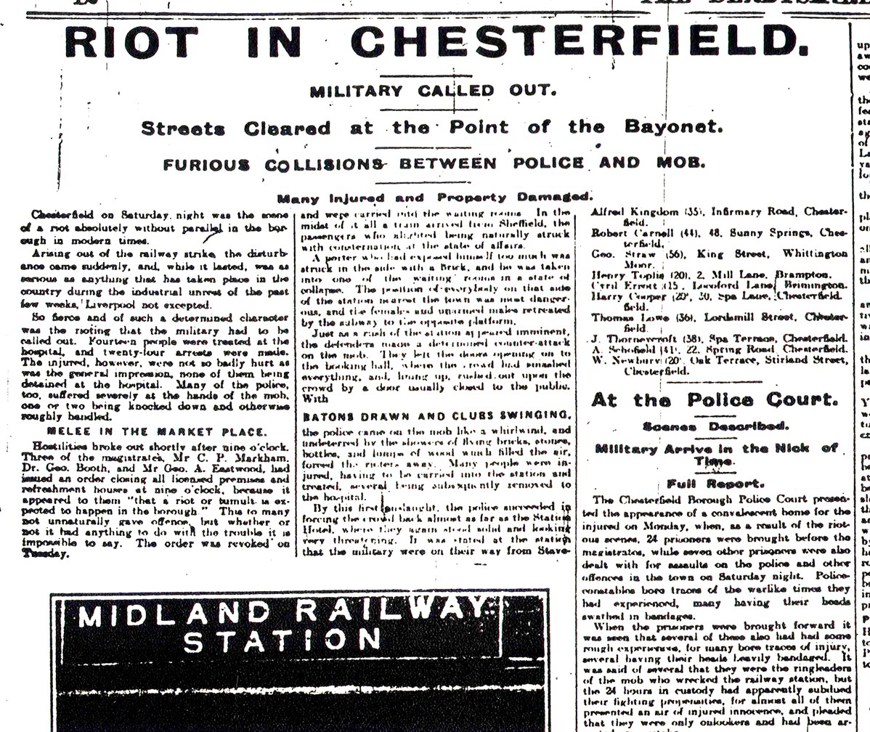

“Chesterfield on Saturday night was the scene of a riot without parallel in the borough in modern times. Arising out of the railway strike ... So fierce and of such a determined character was the rioting that the military had to be called. Fourteen people were treated at the hospital and twenty-four arrests were made.” Derbyshire Times, 26 August 1911. The riot took place at Chesterfield’s main railway station and £300 worth of damage was caused.

“James Smith, charged with begging in Old Road ... made an appearance before the Chesterfield Borough Magistrates and was sent to Derby (Gaol) for seven days ... The prisoner complied with the request to show his hands which had apparently been innocent of soap for a considerable time. The Chief Constable: ‘He will get a bath if he goes to Derby’” Derbyshire Times, 3 February 1912.

“A few minutes before 10pm on Saturday, PC Hood found Fanny Eliza Langley ... crawling about on her hands and knees helplessly drunk in High Street, Chesterfield. On Monday the defendant whose left eye was very much discoloured was charged with being drunk and incapable and pleaded guilty.”

She was fined 5s. Derbyshire Times, Jan 1923.

“Police constable George Henry Turner, of the Chesterfield Borough Police Force, was sentenced to three years penal servitude at Derbyshire Assizes yesterday ...Turner was charged with breaking and entering the shop of William Black, 63 Low Pavement ... and stealing a box of toy furniture, a box of toy road signs, two toy aeroplanes, a pair of cycle pedals and three toy motor vehicles.” Derbyshire Times, February 1939.

“Ernest Charlesworth (17) and Kenneth Hopkinson (27), miner, both of St Augustine’s Road, Chesterfield, were accused of breaking into the pavilion of the Queen’s Park Annexe ... and stealing a pair of plimsolls, a teapot and other articles” Hopkinson was found ‘not guilty’ while Charlesworth was sent to a Borstal (a prison for young offenders) for three years. Derbyshire Times, 5 April 1946.

Maintaining law and order

The early nineteenth century was a time of great social change. Population growth and the movement of people from the countryside to work in industrial towns saw the development of large urban communities.

The old systems of law enforcement were no longer able to cope and so there became a need for an organised, professional police force.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, local community took some responsibility for crime prevention but policing was mainly carried out by constables and night watchmen. Constables were part time, unpaid volunteers appointed by the local ‘manor’ court. Watchmen were employed by local residents to patrol the streets at night.

The first police force was formed in London in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel. This provided a model for the establishment of forces throughout the country.

Watchmen were paid for through contributions from local residents and business people to patrol the streets at night to look out for anything suspicious. Chesterfield operated a night watch, however it does not appear to have been particularly effective. In 1834, a Royal Commission reported “the watching by night is quite inadequate to the protection of property and depredations (thefts) are frequent”.

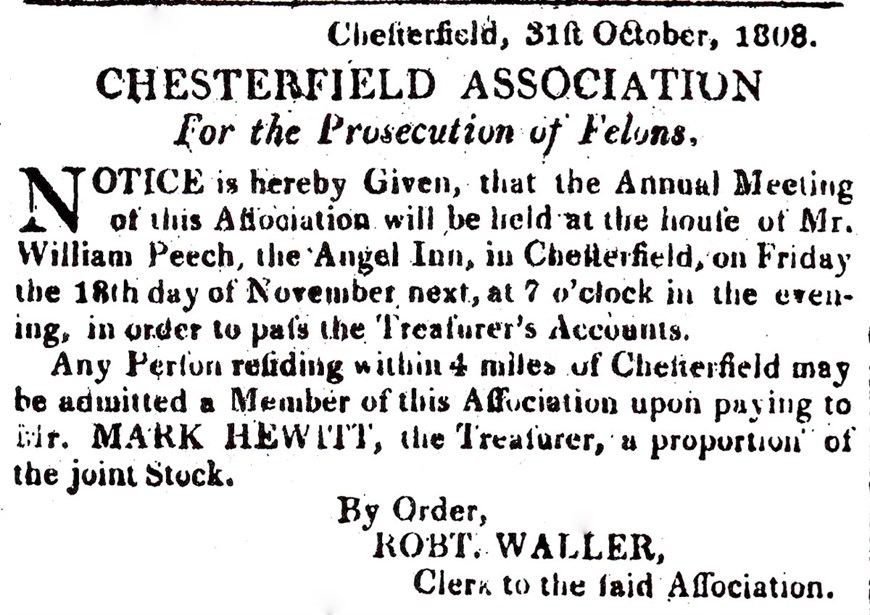

An association for the ‘Prosecution of Felons’ was formed in Chesterfield in 1744. Members paid a yearly fee and in return the organisation offered rewards for information leading to arrests and assistance in paying for the prosecution of offenders. In 1829, the concern about crime prevention was so great that the association appointed seven night watchmen to patrol the streets.

Although constables were responsible for arresting criminals, they did not investigate crimes. Their main role, however, was dealing with public nuisances such as dangerous grates, inadequate gutters and obstructions in the streets for which offenders were fined. At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were five constables in Chesterfield, although more were appointed when necessary. In 1816, thirty-three constables were selected to deal with any discontent as a result of the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Sir Robert Peel formed the country’s first professional police force in London in 1829. The move was not popular however, as people were concerned that it would harm their public liberty. Yet the ‘bobbies’, as they became known, were effective in reducing crime in the capital and within seven years, forces were set up in the rest of the country.

Punishment

The death penalty

At the beginning of the nineteenth century a person could be hanged for over 200 crimes ranging from murder to destroying a bridge. However, the death sentence was not always given, particularly for less serious crimes and there was an increasing reluctance to use it. By 1861 only four crimes warranted death (high treason, murder, piracy and arson in the Royal Dockyards).

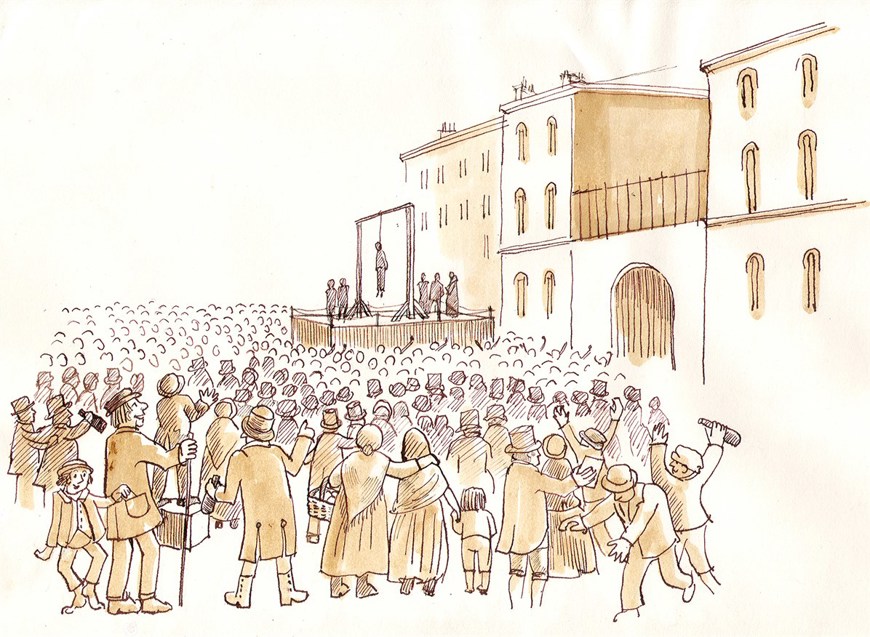

Initially executions were a public event and often drew large crowds, but in 1868 they were carried out within the walls of the prison.

John Platts was hanged in public outside Derby Gaol in April 1847 for the murder of George Collis in the Shambles in Chesterfield. 20,000 people came to watch his execution.

Transportation

Transportation to the British colonies in Australia was seen as an alternative to the death penalty. Offenders were sentenced to life or a specific period of time depending on the seriousness of the crime. Whilst there, convicts worked on government building projects or as unpaid labour in private houses and farms.

Many people from Chesterfield were transported, mainly for theft. In 1826, for example, Thomas Hollingworth, a labourer from Whittington, was sentenced to be transported for seven years after stealing building materials from Henry Dixon.

Transportation could itself be a death sentence. The journey lasted six months and convicts were often locked in cages below decks in insanitary conditions. Many died before they arrived. Transportation ended in 1868.

Corporal punishment

Physical punishment, usually issued alongside a prison sentence, normally took the form of whipping. This was a punishment for crimes such as theft, bigamy or vagrancy (being homeless).

Whipping was carried out in public until 1820 when it was performed within the prison walls and only performed on men. Whipping continued as a sentence until 1948.

David Gregory, a framework knitter, was sentenced to 6 months in Chesterfield’s House of Correction and a public whipping in 1801 for fraud.

Pillory and stocks

The pillory and stocks were punishments intended to shame people. The stocks were used for offences such as drunkenness whereas the pillory, which involved the public throwing things at the prisoner, was used to punish blasphemers, blackmailers and sometimes sexual offenders.

The pillory was abolished in 1815 but use of the stocks continued into the middle of the nineteenth century.

Fines

Fines were issued for a range of petty crimes from poaching to selling beer without a licence as well as breaching the local bye-laws.

John Pollard, for example, was fined 2s 6d for using indecent language on Durrant Road in January 1913.